Shortly before partial knee replacement surgery a few months ago, the hospital pharmacist estimated I might need the oxycodone for 3-4 days after the surgery. Great, I had 10 of the exact pills prescribed from a previous surgery that I never took. Given my supply and the pharmacist’s comment, I didn’t bother to fill the new oxy prescription for the knee surgery. Did I pay a price for that decision!

When I awoke from surgery, they got me out of bed almost immediately and had me walking the halls, almost effortlessly without pain. I felt like a million bucks! Damn, this knee surgery isn’t bad at all, I thought. I later learned that they pump you full of pain killers after surgery so you have a smooth transition to recovery. There’s only one problem with that approach—the drugs eventually wear off.

They send you home with a several-page list of medications and many detailed directions. Take this in the morning with food, this at night, this one 30 minutes before eating, etc. I followed all the directions, with Maureen being extremely helpful in making sure I was taking the right stuff at the right time. Nevertheless, the reality of having someone drill holes into your bones came crashing down soon after arriving home. I was experiencing major-league pain, despite taking the meds. In fact, I’ve never felt pain like this in my life. And I’ve had other surgeries. I slept still as a statue for the first week because the pain was so intense whenever I moved.

I called the ortho nurse to discuss what was going on and what, if anything, I could do about it. I told her the pain was “unbelievable.”

[Watch this short video about the surgery:]

She replied, “Of course it is,” she nearly scolded me. “He drilled into your bones! You have to take the oxycodone.” Within moments, she realized I hadn’t been taking enough of the oxy and hadn’t even filled the hospital prescription. “What? You didn’t fill the prescription?! Why?”

“I don’t want to get addicted,” I confessed.

“You won’t. The fact that you’re concerned about it, means you won’t,” she assured me.

From that day on, I started taking 2 oxy pills every four hours, in addition to about 4 other meds. That stuff works, and I immediately began to get relief. My false sense of pain control cost me at least a week of misery. I was vigilant about the dosing to the point of setting the phone alarm every four hours around the clock so I didn’t take any pills too early or in quantities that exceeded the safe dosing. I frequently woke in pain, staring at the clock to see if I could take that pill. I also made certain the oxy bottle was set aside from all the other meds, and that water was in the cup so I could quickly get my fix in the middle of the night when I was hurting.

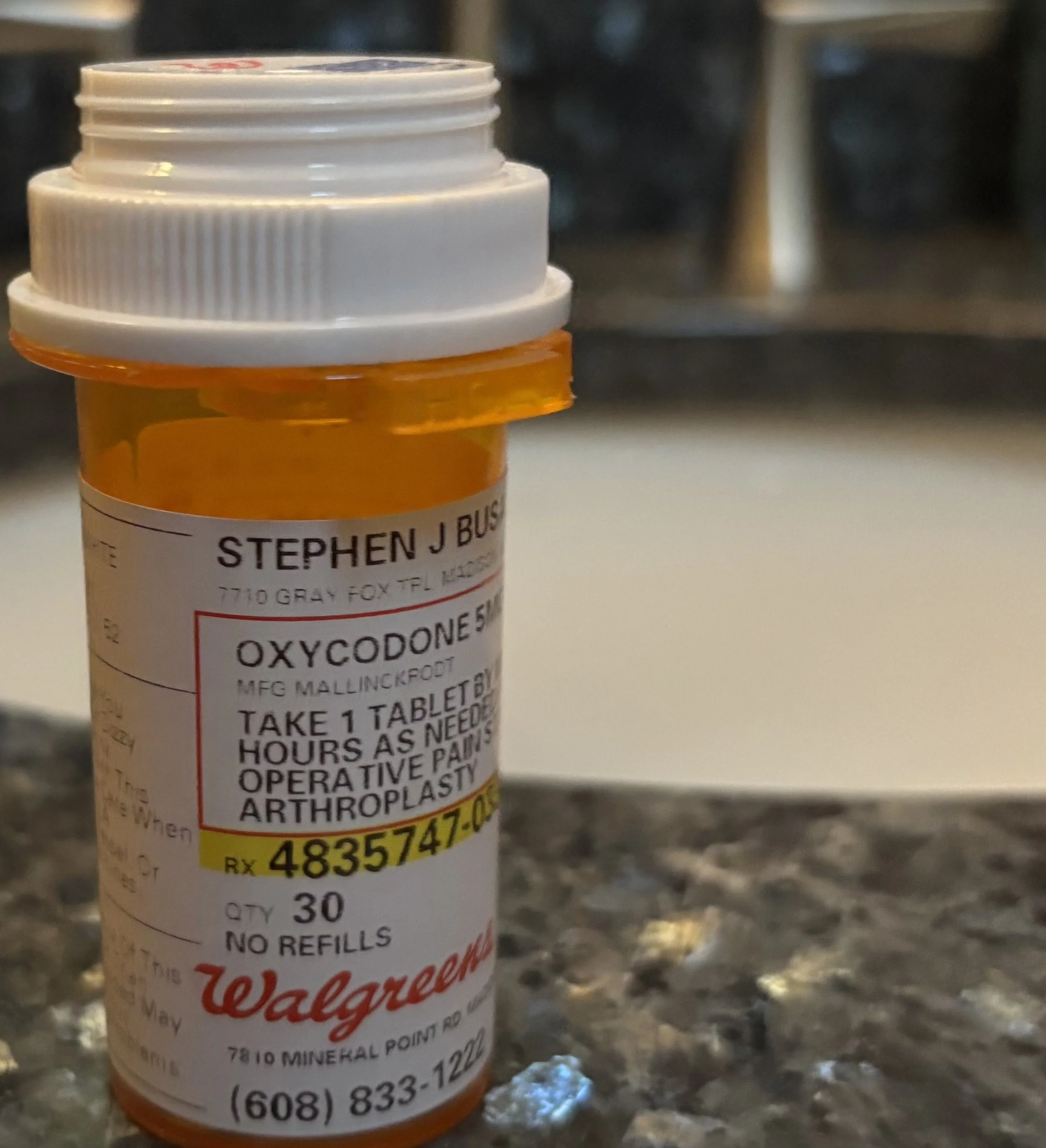

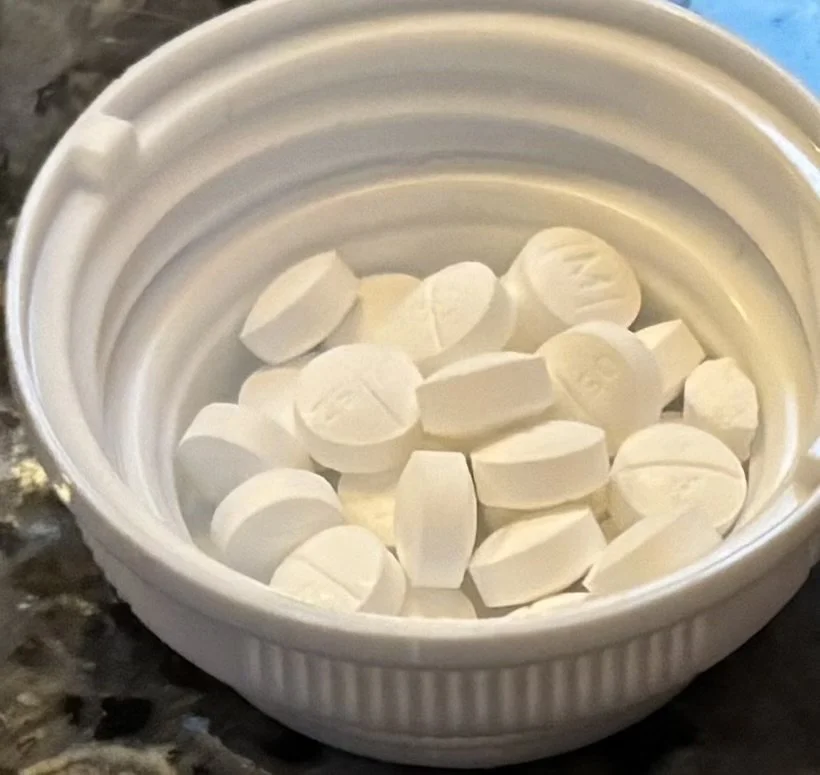

I rather quickly burned through the new oxy prescription the nurse approved and realized more pills were necessary because my pain still was not under control. Ortho wrote me another prescription. I consumed those pills and was doing better, gradually weening myself off them. Now I was taking one oxy every four hours. Then I graduated to one only at night so I could sleep. I called one last time and got another prescription. I asked for just 10 pills because I knew I was close to beating the pain after about 3 weeks. They wrote the full 30-pill prescription anyway. I’m not sure how many I took but the photo shows there are a ton of pills left over.

The knee pain remains but it’s really more like a constant dull ache, alleviated by ibuprofen and acetaminophen. We’ve all heard the admonition to get ahead of the pain. I knew it too, but ignored the warning. I let my fear of addiction get the best of me. The nurse was right, in that if you use the meds to treat the pain within the treatment schedule, you’re standing on solid ground.

I don’t miss the oxy at all and look forward to saying goodbye to the ibuprofen and acetaminophen, too. Amazingly, the 3-4 days of oxy turned into nearly 4 weeks of it!